Cable car systems represent one of the most fascinating feats of modern engineering, combining elegance with brute mechanical force to transport passengers across challenging terrains. At the heart of these systems lies the suspension mechanism, a complex network of steel cables, towers, and cabins that must perform flawlessly under varying environmental and operational conditions. Among the myriad challenges faced by engineers, the control of cable vibrations stands out as a particularly critical area of focus. Unchecked oscillations can lead to accelerated wear, passenger discomfort, and in extreme cases, catastrophic failure. Thus, the development and implementation of effective damping control strategies for steel cable vibrations is not merely an academic exercise—it is an essential practice for ensuring the safety, longevity, and reliability of cable transportation networks worldwide.

The physics of cable vibration is a domain where classical mechanics meets real-world unpredictability. Steel cables, despite their apparent rigidity, are susceptible to a variety of vibrational excitations. These can arise from multiple sources: wind forces, which may induce both steady-state and gust-induced oscillations; mechanical inputs from the drive systems or carriage movements; and even passenger-induced dynamics within the cabins. The cables themselves, often spanning hundreds or even thousands of meters, act like massive strings, with natural frequencies that can be excited by external forces. When these frequencies are matched, resonance occurs, amplifying vibrations to dangerous levels. Understanding these vibrational modes—whether fundamental frequencies or higher harmonics—is the first step toward controlling them. Engineers employ sophisticated modeling techniques, including finite element analysis and computational fluid dynamics, to predict how cables will behave under different conditions and to identify potential vibrational hotspots before they become real-world problems.

Damping, in the context of cable dynamics, refers to the deliberate introduction of energy dissipation mechanisms to reduce the amplitude of vibrations. Unlike rigid structures, where damping might be achieved through material properties alone, cable systems require specialized approaches due to their flexibility and scale. Passive damping systems are among the most commonly employed solutions. These devices operate without external power, relying instead on physical principles to absorb and dissipate vibrational energy. One classic example is the tuned mass damper (TMD), a device consisting of a mass, spring, and damper that is attached to the cable. The TMD is tuned to a specific frequency, and when the cable vibrates at that frequency, the damper oscillates out of phase, effectively counteracting the motion. Another passive approach involves the use of viscoelastic materials wrapped around or integrated into the cable structure. These materials convert mechanical energy into heat, thereby damping vibrations across a broad frequency range. The choice between such methods often depends on factors like the dominant vibration modes, environmental conditions, and maintenance accessibility.

While passive dampers are effective for many scenarios, they have limitations—particularly their inability to adapt to changing conditions. This is where active and semi-active damping systems come into play. Active systems use sensors to monitor cable vibrations in real-time and actuators to apply counter-forces that cancel out unwanted oscillations. These systems can adjust their response based on actual measured data, making them highly effective across a wider range of frequencies and excitation types. However, they require a continuous power supply and sophisticated control algorithms, which can increase complexity and cost. Semi-active systems offer a middle ground: they adjust their damping characteristics using external power but do not directly inject energy into the system like active dampers. For instance, magnetorheological dampers use magnetic fields to change the viscosity of a fluid, altering damping forces almost instantaneously. Such technologies are increasingly being explored for cable car applications where environmental conditions—such as wind speed and direction—change rapidly and unpredictably.

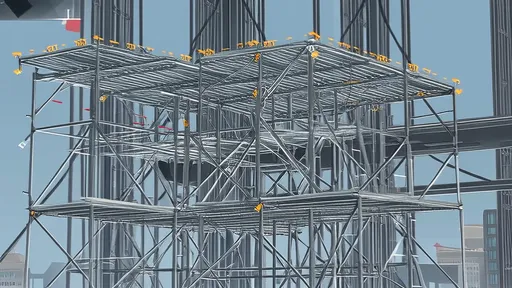

The integration of damping systems into cable car infrastructure is not without its challenges. Engineers must consider the interplay between damping devices and other components of the suspension system. For example, the attachment points for dampers must be structurally sound to withstand the forces involved, yet minimally invasive to avoid compromising the cable’s integrity. Environmental factors also play a crucial role; equipment must operate reliably in extreme temperatures, high humidity, and corrosive conditions, such as those found in alpine or coastal regions. Moreover, maintenance access can be a significant issue, especially for cables strung across remote or inaccessible areas. Thus, the design of damping solutions often involves trade-offs between performance, durability, and practicality. Field testing and long-term monitoring are essential to validate theoretical models and ensure that damping systems perform as intended over the lifespan of the installation.

Recent advancements in materials science and digital technology are opening new frontiers in cable vibration control. Smart materials, such as shape memory alloys and piezoelectric composites, are being investigated for their potential to provide lightweight, adaptive damping. These materials can change their properties in response to electrical or thermal stimuli, offering new ways to manage vibrations without bulky mechanical components. At the same time, the rise of the Internet of Things (IoT) and big data analytics is transforming how cable systems are monitored and maintained. Networks of wireless sensors can provide continuous, high-resolution data on cable dynamics, enabling predictive maintenance and real-time adjustments to damping parameters. Machine learning algorithms are being trained to recognize patterns in vibration data, potentially allowing for even more precise and proactive control strategies. These innovations promise to make future cable car systems not only safer but also more efficient and cost-effective to operate.

Looking ahead, the field of cable vibration damping is poised for continued evolution. As urban areas become more congested and tourism in rugged terrain increases, the demand for cable transportation is likely to grow. This will drive further innovation in damping technologies, with an emphasis on sustainability, resilience, and integration with smart city infrastructures. Researchers are already exploring concepts like energy-harvesting dampers that convert vibrational energy into electricity, which could power sensors or other low-energy devices on the cable system. There is also growing interest in bio-inspired designs—for example, damping mechanisms that mimic the shock-absorption properties of natural systems. Whatever the direction, one thing is clear: the silent, unseen work of damping steel cable vibrations will remain a cornerstone of cable car safety and performance for years to come.

In conclusion, the damping control of steel cable vibrations in cable car suspension systems is a multifaceted engineering discipline that blends theoretical insight with practical innovation. From passive devices that have proven their worth over decades to cutting-edge active systems powered by artificial intelligence, the tools available to engineers are more powerful than ever. Yet the core objective remains unchanged: to ensure that these aerial pathways operate smoothly, safely, and reliably, no matter what forces they face. As technology advances and our understanding of cable dynamics deepens, we can expect ever more sophisticated solutions to emerge—each contributing to the enduring appeal and utility of cable car transportation around the globe.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025