In the quiet depths of ocean trenches and the vast expanse of darkened caves, nature has engineered one of its most sophisticated sensory adaptations: echolocation. This biological sonar system, employed by creatures ranging from bats to dolphins, represents a remarkable convergence of physics, biology, and environmental adaptation. The underlying principle—using sound waves and their returning echoes to construct a detailed mental map of the surroundings—is a testament to evolutionary ingenuity. For decades, scientists have been captivated by this phenomenon, not merely as a biological curiosity but as a complex natural algorithm for spatial reasoning and object detection. The study of these acoustic encounters, specifically the calculation and interpretation of reflected sound waves, opens a window into both the natural world and potential technological applications.

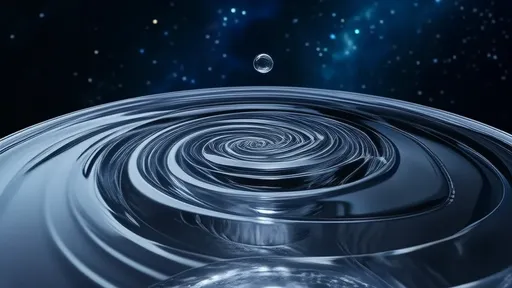

The fundamental mechanics of echolocation begin with the emission of a sound wave. This is no random noise; it is a carefully calibrated signal, often a click or a chirp, tailored to the environment and the task at hand. In dolphins, for instance, these clicks are produced by nasal sacs and focused through the melon—an organ in the forehead that acts as an acoustic lens. The sound pulses travel through water or air at speeds determined by the medium’s density and temperature, spreading out until they encounter an object. Upon impact, a portion of the sound energy is reflected back toward the emitter. The key to echolocation lies in the precise detection and analysis of these returning echoes. The time delay between emission and return provides critical information about distance, while variations in frequency and amplitude reveal details about the object’s size, shape, texture, and even movement.

What makes this process truly extraordinary is the neural computation involved. The brain of an echolocating animal must perform rapid, real-time calculations to translate acoustic data into a coherent spatial image. For a bat chasing a moth through dense foliage, this means processing echoes in milliseconds, distinguishing the faint rustle of insect wings from the clutter of leaves and branches. This requires not only acute hearing but also an advanced auditory cortex capable of filtering, integrating, and interpreting overlapping sound signals. Researchers have found that certain species of bats can detect delays as short as a few microseconds, allowing them to resolve details finer than the width of a human hair. This precision is achieved through a combination of specialized neurons tuned to specific time delays and frequencies, creating a neural map of the environment that is both dynamic and incredibly detailed.

In the marine realm, dolphins and toothed whales face an even greater challenge. Water is a denser medium than air, transmitting sound faster and over longer distances, but it also introduces complications like turbulence, temperature gradients, and suspended particles that can scatter or distort echoes. To overcome this, dolphins emit a broad spectrum of clicks, from low-frequency sounds that travel far and penetrate murky waters to high-frequency signals that provide high-resolution details at closer ranges. Their ability to discriminate between objects of similar size and composition—such as distinguishing a fish from a rock—demonstrates a sophisticated level of echo processing that continues to intrigue bioacousticians. Recent studies suggest that dolphins may even use their iconic whistles not just for communication but also to enhance their echolocation by modulating the properties of their outgoing signals based on environmental feedback.

The mathematical underpinnings of echolocation involve principles from wave physics and signal processing. The echo’s travel time, given by t = 2d/c, where d is the distance to the object and c is the speed of sound, is the most straightforward metric. However, this is merely the starting point. The Doppler shift—a change in frequency caused by relative motion between the emitter and the target—adds another layer of information, enabling the animal to gauge whether an object is approaching or receding and at what velocity. Furthermore, the amplitude and spectral content of the echo depend on the object’s acoustic impedance, surface roughness, and geometry. A smooth, hard surface will produce a stronger, clearer echo than a soft, irregular one, and the subtle distortions in the returning wavefront can reveal intricate structural details. This complex interplay of variables means that echolocation is not a passive reception of signals but an active, adaptive process of inquiry and interpretation.

Human attempts to replicate this ability have led to the development of sonar and lidar systems, which are now staples in fields ranging from navigation to medicine. Yet, even the most advanced artificial systems pale in comparison to the efficiency and versatility of biological echolocation. Engineers and roboticists are increasingly turning to nature for inspiration, developing algorithms that mimic the neural networks of bats or dolphins to improve autonomous vehicles and underwater drones. These bio-inspired systems often employ machine learning to adapt to noisy environments, much like their biological counterparts. For example, some researchers have created software that uses generative models to predict and compensate for echo distortion in cluttered settings, enhancing object detection accuracy. This synergy between biology and technology highlights the potential for echolocation principles to revolutionize fields like robotics, medical imaging, and even assistive devices for the visually impaired.

Beyond practical applications, the study of echolocation raises profound questions about perception and cognition. It challenges the human-centric view of reality, reminding us that other species experience the world through sensory modalities that are alien to us. For an echolocating animal, sound is not just a medium for communication but a primary tool for seeing—a way to paint the world in echoes. This auditory spatial awareness is so refined that blind humans have been known to develop a form of echolocation using mouth clicks, navigating their environments with surprising agility. These individuals often show activation in visual cortex areas when processing echoes, suggesting that the brain can repurpose regions typically dedicated to vision for auditory spatial mapping. This plasticity underscores the universality of the computational principles underlying echolocation, transcending species and sensory boundaries.

As research progresses, new discoveries continue to refine our understanding of echolocation. Cutting-edge tools like ultra-high-speed microphones and neural recording devices allow scientists to capture the intricacies of acoustic signals and brain activity in unprecedented detail. For instance, recent experiments with bats have revealed that they can adjust their call patterns on the fly, switching from slower, scanning pulses to rapid, targeted bursts when closing in on prey. This dynamic control indicates a level of cognitive flexibility that was previously underestimated. Similarly, studies on dolphins have shown that they can recognize complex objects through echolocation alone, identifying shapes and materials with accuracy that rivals visual identification. These findings not only deepen our appreciation for these animals but also provide valuable insights for improving artificial sensing systems.

The environmental implications of echolocation are also gaining attention, particularly as human-generated noise pollution increasingly infiltrates natural soundscapes. Oceanic noise from shipping, sonar, and industrial activity can mask the delicate echoes that dolphins and whales rely on, disrupting their ability to hunt, navigate, and communicate. In air, urbanization and infrastructure development alter acoustic environments, affecting bat populations that depend on echolocation for survival. Conservation efforts now recognize the need to preserve not just physical habitats but also the acoustic conditions essential for these species. This has led to initiatives like quieting ship engines in critical marine areas or designing wildlife-friendly infrastructure that minimizes acoustic interference. Understanding echolocation is thus not only a scientific pursuit but also an ethical imperative, highlighting our responsibility to safeguard the sensory worlds of other creatures.

In the grand tapestry of natural innovation, echolocation stands out as a brilliant synthesis of physics, biology, and computation. It is a living testament to the power of adaptation, showing how life can harness fundamental laws of nature to overcome environmental challenges. From the mathematical precision of echo timing to the neural artistry of spatial mapping, every aspect of this ability reflects a deep, inherent intelligence. As we continue to unravel its mysteries, we are not only learning about bats and dolphins but also about the very nature of perception itself. The echoes that guide these creatures through darkness carry lessons that resonate far beyond the animal kingdom, offering insights that could shape the future of technology and our relationship with the natural world. In listening to their sounds, we may yet learn to see with new ears.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025