Crazing in ceramic glazes, often perceived as a flaw in industrial production, represents one of the most poetic and deliberate artistic expressions in the world of studio ceramics. This intricate network of fine lines, known as crackle or crackling, emerges from the calculated interplay between the clay body and the glaze—a dance of tension and release governed by the critical principle of thermal expansion. The art lies not in preventing this phenomenon, but in mastering it, transforming a potential weakness into a celebrated feature of depth and history.

The entire process is a meticulous orchestration of chemistry and physics, beginning in the fiery heart of the kiln. As the ceramic piece is heated to its maturation temperature, both the clay body and the glaze layer melt and fuse. Upon cooling, a fundamental physical property takes center stage: the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE). This coefficient measures how much a material expands when heated and contracts when cooled. For a stable, flawless finish, the ideal scenario is for the glaze to have a slightly lower CTE than the clay body. As they cool together, the clay contracts slightly more than the glaze, placing the glaze under a state of compression, which results in a strong, seamless surface.

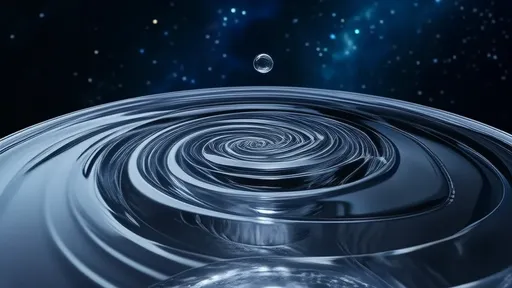

However, the artist seeking the beauty of crackle deliberately inverts this relationship. By formulating a glaze with a significantly higher CTE than the underlying clay body, the stage is set for crazing. During cooling, the glaze wants to contract more than the body is contracting. But because it is firmly bonded to the rigid body, it cannot shrink freely. This creates immense tensile stress within the glassy glaze layer. Eventually, this stress must be relieved, and it finds its escape through the formation of a network of microscopic fractures—the crazing pattern. It is a controlled and intended failure, a release of pent-up energy that etches a permanent record of the thermal history onto the surface of the piece.

The character of the crackle network is not random; it is a direct signature of the artist's choices. The specific chemical composition of the glaze is the primary brushstroke. High concentrations of fluxes like sodium and potassium, which have high expansion rates, are classic drivers for crazing. A glaze rich in sodium, for instance, will almost certainly produce a pronounced crackle. The thickness of the glaze application also plays a crucial role; a thicker layer will develop a more prominent and deeper network than a thin, wash-like application. Furthermore, the cooling cycle itself is a tool. A rapid quench from a high temperature can shock the glaze into a more dramatic and immediate crackle, while a very slow, controlled cool might yield a finer, more subtle web.

For centuries, and most famously in Chinese Ge ware and Guan ware of the Song Dynasty, this technique was refined to an ethereal level. Chinese potters elevated crazing from a physical occurrence to a central aesthetic philosophy. They developed methods to accentuate the lines, often by rubbing pigments like ink or tea into the fractures, which would then stain the underlying clay, making the intricate pattern visible and permanent. This practice highlighted the passage of time and the concept of an object acquiring beauty through use and age, a value deeply embedded in East Asian artistic traditions. The crackle was not a finish but a beginning—a canvas that would evolve and deepen in character long after it left the kiln.

In contemporary studio ceramics, the embrace of crackle is both a homage to these traditions and a frontier for innovation. Modern artists wield a sophisticated understanding of material science to predict and manipulate outcomes. They might combine a dark, iron-rich clay with a pale, crazing glaze, knowing the contrasting color will seep into the cracks to create a bold, graphic network. Others might employ multiple glaze layers with different expansion coefficients to achieve complex, overlapping crackle patterns of varying scale and color. The post-firing treatment has also expanded beyond traditional stains to include metallic oxides, lusters, or even repeated firings to allow new glazes to flow into the existing cracks.

Beyond its visual appeal, the crackle glaze carries a profound metaphorical weight. It speaks to the beauty of imperfection, a core tenet of the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which finds majesty in the imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. The cracks are a record of stress, a map of the object’s journey through the transformative fire. They are a visible acceptance of change and a symbol of resilience—the piece did not shatter under internal pressure but instead found a new way to exist, bearing its history with grace. It tells a story of vulnerability and strength, making each piece uniquely narrative.

From a technical conservation perspective, crazing presents a double-edged sword. In a deliberately crafted art piece, the network is stable and part of its identity. However, in functional ware or archaeological objects where crazing was unintended, it can be a conservation concern. The micro-fissures increase the surface area and can trap moisture, acids, and dirt, potentially leading to long-term deterioration or staining. For the artist creating functional pieces with crackle glazes, this necessitates careful consideration and often a disclaimer, as the surface is not as hygienically sealed as a non-crazed glaze.

Ultimately, the art of ceramic glaze crazing is a sublime negotiation between control and surrender. The artist controls the chemistry, the application, and the firing, setting all the parameters for the phenomenon to occur. But the final pattern—the specific arrangement of lines, the subtle variations in spacing and depth—is surrendered to the inherent properties of the materials and the unpredictable dynamics of the kiln. This collaboration between human intention and material behavior is what gives each crazed surface its unique soul. It is a permanent capture of a transient moment of stress and release, a frozen echo of the kiln's heat, and a testament to the fact that true beauty often lies in the graceful acceptance of a flaw.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025