In the hushed auditorium of a televised lottery drawing, the mechanical whir of numbered balls tumbling against each other creates a peculiar symphony of chance. To the average viewer, it is a spectacle of randomness, a moment where fortune seems to descend from the heavens to select a handful of winners. Yet, beneath the polished surface of this modern ritual lies a profound and often misunderstood dialogue between pure mathematics and the human desire for a life-altering break. The lottery machine is not merely a box of fate; it is a meticulously engineered device operating under the immutable laws of probability, a stage where the cold, precise logic of combinatorics performs a tantalizing dance with our warm, hopeful perception of luck.

The very design of a lottery draw machine is a testament to the pursuit of true randomness. These are not simple containers but sophisticated pieces of engineering. The balls are crafted to be perfectly uniform in weight and size, often made from a special closed-cell foam or a lightweight polymer to minimize any bias from static electricity or minor imperfections. The chamber itself is designed with paddles or jets of air to ensure a chaotic and turbulent mixing process. Engineers and mathematicians work in tandem to create a system where each ball has a statistically equal opportunity to be selected at the moment the draw is made. This physical engineering is the first layer of probability in action, a brute-force approach to simulating the theoretical "fairness" of a random number generator. It is an attempt to build a perfect, impartial physical universe inside a clear plastic dome.

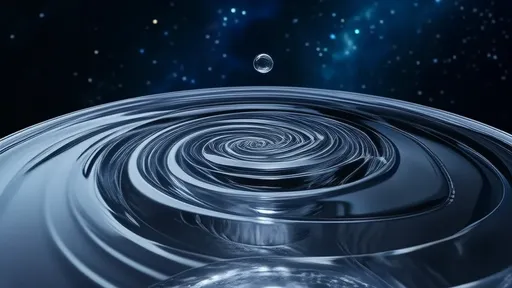

This physical randomness is the gateway to the abstract world of probability theory. The odds of winning a major lottery, often stated in the hundreds of millions to one, are not plucked from thin air. They are calculated with surgical precision using the mathematics of combinations. The question a lottery asks is fundamentally combinatorial: how many ways can you choose, for example, 6 numbers out of a possible 49? The answer is given by a formula known as the binomial coefficient, resulting in a specific, astronomically large number. This number represents every single possible unique ticket that could be played. When you buy a ticket, you are not just buying a sequence of numbers; you are purchasing one of these millions of distinct possibilities. The draw, therefore, is not about your numbers being "chosen," but about the single combination that is randomly selected matching the one specific combination you hold. The probability is breathtakingly small because the sample space—the total number of outcomes—is breathtakingly large.

This immense gap between the single winning ticket and the millions of losing ones creates a powerful psychological phenomenon known as the "availability heuristic." Our brains are not wired to intuitively grasp such vast numbers. We understand the joy of a winner we see on television; that outcome is available and vivid in our minds. We cannot, however, easily conceptualize the silent, collective sigh of the tens of millions of losers whose stories go untold. This cognitive bias fuels the enduring appeal of the lottery. The near-certainty of loss is a silent, abstract statistic, while the dream of victory is a loud, colorful, and emotionally charged narrative. We are not betting against the odds; we are buying a well-defined period of hope, a tangible dream to hold onto until the next drawing. The lottery, in this sense, sells more than a chance; it sells a story.

Furthermore, the human mind is a pattern-recognition engine, often to a fault. This leads players to employ strategies that probability squarely debunks. People will avoid numbers that have recently been drawn, believing they are "due" for a rest—a manifestation of the Gambler's Fallacy, which mistakenly applies the law of large numbers to short, independent sequences. Conversely, others will play frequently drawn numbers, believing in a "hot streak." Some choose their numbers based on birthdays, anniversaries, or other significant dates, clustering their selections in the lower range (1-31) and ignoring the higher numbers, a tactic that is emotionally satisfying but mathematically irrelevant. In a truly random draw, every combination, from 1-2-3-4-5-6 to 13-27-39-41-48-53, has the exact same probability of being drawn. The machine has no memory, no sentiment, and no sense of pattern. It is the ultimate arbiter of impartiality.

The intersection of the lottery machine and probability is perhaps most ironic when considering the concept of expected value. For a typical lottery, the expected value of a $2 ticket is almost always negative, meaning that over the long term, a player will inevitably lose money. This is because the prize pool is only a fraction of the total revenue from ticket sales, with the rest funding administrative costs, retailer commissions, and state programs. However, this cold economic reality is temporarily suspended when the jackpot grows to a record size, often into the hundreds of millions or even billions. At these dizzying heights, the expected value can—theoretically—tip into positive territory, making a purchase a rational bet from a purely mathematical standpoint. This creates a fascinating feedback loop: the worse the odds are (leading to rollovers), the larger the jackpot grows, which in turn attracts more players driven by the improved statistics, making the odds of having to split the prize even higher. It is a beautiful and chaotic cycle of mathematics and mass psychology.

Ultimately, the lottery drawing machine stands as a powerful cultural symbol. It is a physical manifestation of a mathematical principle, a box where probability becomes performative. It translates the abstract, intimidating equations of combinatorics into a simple, visceral event that anyone can understand: a ball pops up, a number is called. It democratizes chance, offering the same minuscule sliver of hope to the PhD statistician as it does to the casual dreamer. The machine itself is neutral, a blind arbiter governed by the laws of physics and math. The meaning, the hope, the dreams of escape and transformation—that is all projected onto it by us. We see a lucky meeting of numbers; probability theory sees one inevitable outcome in a sea of possibilities. The true magic lies not in the machine's operation, but in its unique ability to make us feel, for a brief moment, that the coldest, most rigid logic in the universe might just be capable of delivering a miracle.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025